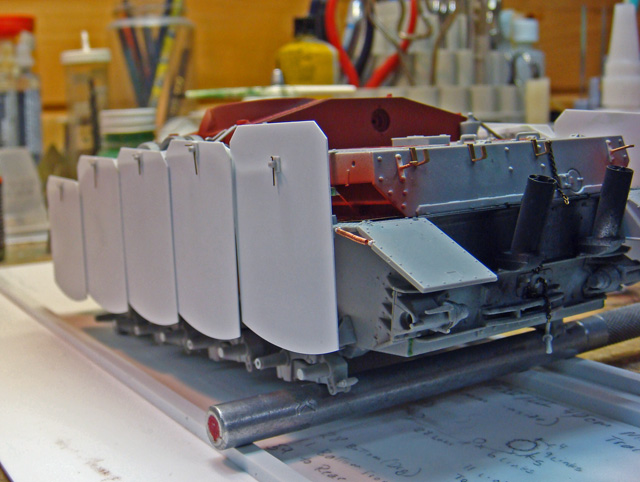

For the StuG, I assumed that the basic DML kit was either correct or at least proportionally accurate. I used used key points on the hull and suspension, taken from the photos, to identify the corresponding key points on the geometry of the swinging Schurtzen frame and parts. I then took measurements from those points on the kit to dimension the frame and parts for the build.

In this case, the kit, itself, provided the “scaled measurements” for the scratch built parts.

The factory photo of the StuG shows how on even an oblique shot, key points can be transferred from the photo and matched to points that can be identified on the kit. The actual measurements can then be taken from the kit to dimension the new parts.

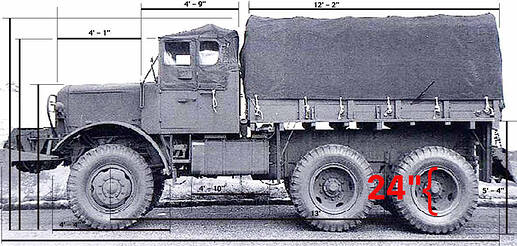

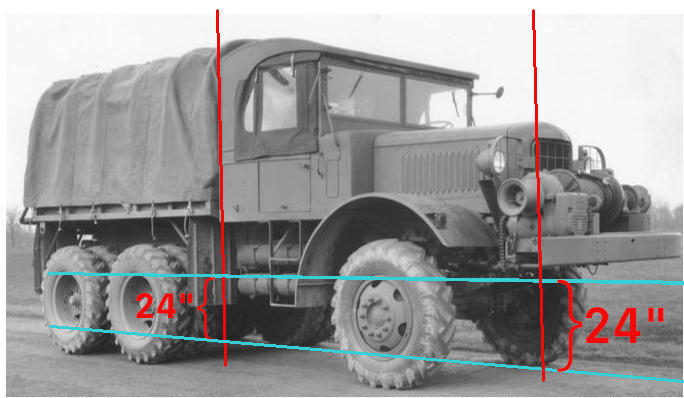

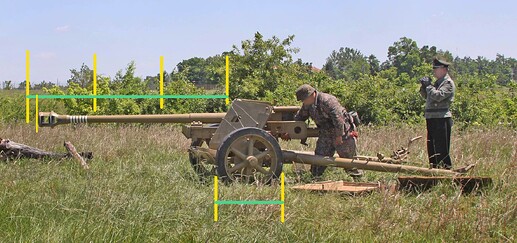

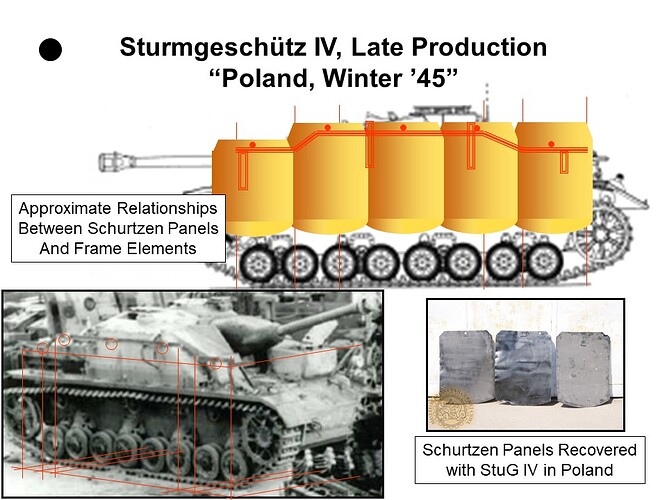

A point to note is that on the side, because the Schurtzen frame overhangs the fenders and suspension, the key points on the frame are taken from vertical lines that are drawn down to the ground level. These points are then taken back inboard along the ground to the corresponding key points on the suspension that the measurements will be taken from.

(Note that the lines on the ground that trace back to the suspension are drawn longer than needed in this example. The point at which they first touch the suspension components - either the track or the wheels - is really all that’s important. Since this was originally done just for my own use, I didn’t worry about having to explain this later.)

As long as the lines are kept parallel to the lines of perspective on the vehicle in the photo, their intersection points will match (at least precisely enough for the purpose) the corresponding points on the model. Taking the measurements from those points on the model is then a simple matter.

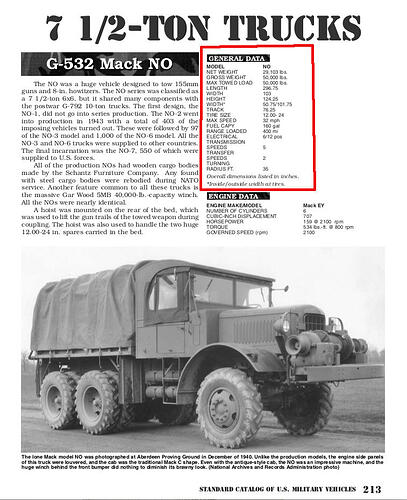

The challenge for this bit of scratch building (the swinging Schurtzen on the StuG IV) was that the only really useful references were wartime photos, all taken from various distances and perspectives. The dimensions of the actual vehicle were never in question. What was necessary here was to “reverse engineer” the design of the Schurtzen frame and parts and then dimension them accurately enough to build in 1/35 scale. There were several published sets of scaled drawings or renderings of the “swingers” which proved completely inaccurate. For many years, it was assumed that the Schurtzen plates were graduated in height - shorter in the front, taller in the rear. (Actually, only the front most panels are shorter to allow the driver to see over them with his head out of his hatch. All of the others are the same height.) This was based on a misunderstanding of the photo of the StuG being loaded on the barge. However, once you draw some lines on the photo and take into account the effects of perspective and the vanishing point, it becomes clear that all of these previously published drawings and renderings were very wrong.

Regards to tabulated wheel sizes, all of the Spielberger books contain appendices for the vehicles covered in them in which the road wheel sizes are listed. The same is true for most of the US AFVs that are covered in the Hunnicutt books. The appendices list the road wheel sizes.