Not linked to me, but I just watched an amazing film, based on a journal of the events. Its about a USMC Col, who acts as the escort of a fallen Marine during the 2nd Iraq War. Its about the lads trip once he returns to US soil and back to his family. Its a hell of a film and its emotional. if you have not seen it. Watch it.

I feel like I might have seen it years ago. Did have some friends do different parts of the process. ![]()

Its from 2009 so you may well have. I only saw a YouTube clip of it a few days ago and it intrigued me. I have to take my hat off to the US and Canada. They know how to treat their fallen once they are repatriated.

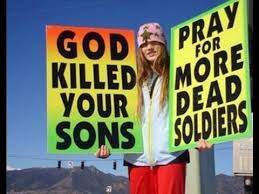

We have a group the “Westborough Baptist Church” that have another take on the fallen.

They show up at funerals to shout their message to the attendees.

Fine folk those West Borough Baptists.

how have they not been shut down for hate speech.

I dont have to say anything as you should know me well enough to know exactly how I would deal with them.

Swerved to avoid a cat that suddenly dashed across the road and then disappeared into the bushes?

The Westboro Baptist Church are mostly one family spawned by the late Fred Phelps; like him many of them are lawyers and appear to revel in litigation. Most findings against them in lower courts are reversed by higher courts on First Amendment grounds. Although fervently antisemitic they appear not to be otherwise racist (before his disbarment Fred Phelps worked on civil rights cases on behalf of African-American clients) but denounce certain nations - I believe these include Sweden and Australia… Phelps himself was excommunicated by the WBC shortly before his death (possibly because some form of dementia had caused a softening in his views) while other members of the family have left of their own accord.

Regards,

M

Guys - Can we please keep on track with this. Its only about the film, nothing else please.

Good to know that we, i.e. Sweden, must be doing something right ![]()

Further reading on the why’s and what’s:

If I had any religious beliefs I would pray for their deity to immediately let the souls of those Westboro baptists leave this earthly existence.

I do feel touched by the way fallen US soldiers are honoured,

I just wish the surviving veterans,

many suffering from physical and/or mental wounds,

would be properly cared for.

I get the impression that there is way too little ‘Thank you for your service’

Westboro Baptist Church also protested the horror movie “Red State” because it was inspired by them…

Cheers,

M

I have escorted a Soldier’s remains home. It is THE most solemn Duty of my career.

The movie is very good, and a close representation of what the Escort Officer experiences.

Thank you for carrying out that Duty.

Looking at old emails for a different reason and this movie popped up talking about the premiere on HBO in Feb 2009.

Taking Chance

Marine Corps Gazette - Quantico

Author: Michael R Strobl

Date: Jul 2004

The Nation mourns.

Chance Phelps was wearing his Saint Christopher medal when he was killed on Good Friday. Eight days later I handed the medallion to his mother. I didn’t know Chance before he died. Today, I miss him.

Over a year ago I volunteered to escort the remains of Marines killed in Iraq should the need arise. The military provides a uniformed escort for all casualties to ensure they are delivered safely to the next of kin and are treated with dignity and respect along the way. Thankfully, I hadn’t been called on to be an escort since Operation IRAQI FREEDOM began. The first few weeks of April, however, had been tough ones for the Marines. On the Monday after Easter I was reviewing Department of Defense press releases when I saw that a PFC Chance Phelps was killed in action outside of Baghdad. The press release listed his hometown-the same town I’m from. I notified our battalion adjutant and told him that, should the duty to escort PFC Phelps fall to our battalion, I would take him. I didn’t hear back the rest of Monday and all day Tuesday until 1800. The battalion duty noncommissioned officer called my cell phone and said I needed to be ready to leave for Dover Air Force Base (AFB) at 1900 in order to escort the remains of PFC Phelps.

Before leaving for Dover I called the major who had the task of informing Phelps’ parents of his death. The major said the funeral was going to be in Dubois, WY. (It turned out that PFC Phelps only lived in my hometown for his senior year of high school.) I had never been to Wyoming and had never heard of Dubois.

With two other escorts from Quantico, I got to Dover AFB at 2330 on Tuesday night. First thing on Wednesday we reported to the mortuary at the base. In the escort lounge there were about half a dozen Army soldiers and about an equal number of Marines waiting to meet up with “their” remains for departure. PFC Phelps was not ready, however, and I was told to come back on Thursday. Now at Dover, with nothing to do and a solemn mission ahead, I began to get depressed.

1 was wondering about Chance Phelps. 1 didn’t know anything about him, not even what he looked like. I wondered about his family and what it would be like to meet them. I did pushups in my room until I couldn’t do any more.

On Thursday morning I reported back to the mortuary. This time there was a new group of Army escorts and a couple of the Marines who had been there Wednesday. There was also an Air Force captain there to escort his brother home to San Diego.

We received a brief covering our duties, the proper handling of the remains, the procedures for draping a flag over a casket and, of course, the paperwork attendant to our task. We were shown pictures of the shipping container and told that each one contained-in addition to the casket-a flag. I was given an extra flag since Phelps’ parents were divorced. This way they would each get one. I didn’t like the idea of stuffing the flag into my luggage, but I couldn’t see carrying a large flag, folded for presentation to the next of kin, through an airport while in my Alpha uniform. It barely fit into my suitcase.

It turned out that I was the last escort to leave on Thursday. This meant that I repeatedly got to participate in the small ceremonies that mark all departures from the Dover AFB mortuary. Most of the remains are taken from Dover AFB by hearse to the airport in Philadelphia for air transportation to their final destination. When the remains of a service member are loaded onto a hearse and ready to leave the Dover mortuary, there is an announcement made over the building’s intercom system. With the announcement all service-members working at the mortuary, regardless of Service branch, stop work and form up along the driveway to render a slow ceremonial salute as the hearse departs.

Escorts also participated in each formation until it was their time to leave.

On this day there were some civilian workers doing construction on the mortuary grounds. As each hearse passed they would stop working and place their hardhats over their hearts. This was my first sign that my mission with PFC Phelps was larger than the Marine Corps and that his family and friends were not grieving alone.

Eventually I was the last escort remaining in the lounge. The Marine master gunnery sergeant in charge of the Marine liaison there came to see me. He had Chance Phelps’ personal effects. he removed each item-a large watch, a wooden cross with a lanyard, two loose dog tags, two dog tags on a chain, and a Saint Christopher medal on a silver chain. Although we had been briefed that we might be carrying some personal effects of the deceased, this set me aback.

Holding his personal effects, I was starting to get to know Chance Phelps.

Finally, we were ready. I grabbed my bags and went outside. I was somewhat startled when I saw the shipping container, loaded three-quarters of the way into the back of a black Chevy Suburban that had been modified to carry such cargo. This was the first time I saw my “cargo,” and I was surprised at how large the shipping container was. The master gunnery sergeant and I verified that the name on the container was Phelps’, then they pushed him the rest of the way in and we left. Now it was PFC Chance Phelps’ turn to receive the military-and construction workers’-honors. he was finally moving toward home.

As I chatted with the driver on the hour-long trip to Philadelphia, it became clear that he considered it an honor to be able to contribute in getting Chance home. he offered his sympathy to the family. I was glad to finally be moving, yet apprehensive about what things would be like at the airport. I didn’t want this package to be treated like ordinary cargo, but I knew that the simple logistics of moving around a box this large would have to overrule my preferences.

When we got to the Northwest Airlines cargo terminal at the Philadelphia airport, the cargo handler and hearse driver pulled the shipping container onto a loading bay while I stood to the side and executed a slow salute. Once Chance was safely in the cargo area, and I was satisfied that he would be treated with due care and respect, the hearse driver drove me over to the passenger terminal and dropped me off.

As I walked up to the ticketing counter in my uniform, a Northwest employee started to ask me if I knew how to use the automated boarding pass dispenser. Before she could finish, another ticketing agent interrupted her. He told me to go straight to the counter then explained to the woman that I was a military escort. She seemed embarrassed. The woman behind the counter already had tears in her eyes as I was pulling out my government travel voucher. She struggled to find words but managed to express her sympathy for the family and thank me for my service. She upgraded my ticket to first class.

After clearing security I was met by another Northwest Airline employee at the gate. She told me that a representative from cargo would be up to take me down to the tarmac to observe the movement and loading of PFC Phelps. I hadn’t really told any of them what my mission was, but they all knew.

When the man from the cargo crew met me he, too, struggled for words. On the tarmac he told me stories of his childhood as a military brat and repeatedly told me that he was sorry for my loss. I was starting to understand that even here in Philadelphia, far away from Chance’s hometown, people were mourning with his family.

On the tarmac the cargo crew was silent except for occasional instructions to each other. I stood to the side and saluted as the conveyor moved Chance to the aircraft. I was relieved when he was finally settled into place. The rest of the bags were loaded, and I watched them shut the cargo bay door before heading back up to board the aircraft.

One of the pilots had taken my carryon bag himself and had it stored next to the cockpit door so he could watch it while I was on the tarmac. As I boarded the plane I could tell immediately that the flight attendants had already been informed of my mission. They seemed a little choked up as they led me to my seat.

About 45 minutes into our flight I still hadn’t spoken to anyone except to tell the first class flight attendant that I would prefer water. I was surprised when the flight attendant from the back of the plane suddenly appeared and leaned down to grab my hands. She said, “I want you to have this,” as she pushed a small gold crucifix with a relief of Jesus into my hand. It was her lapel pin, and it looked somewhat worn. I suspected it had been hers for quite some time. That was the only thing she said to me the entire flight.

When we landed in Minneapolis, I was the first one off the plane. The pilot himself escorted me straight down the side stairs of the exit tunnel to the tarmac. The cargo crew there already knew what was on this plane. They were unloading some of the luggage when an Army sergeant, a fellow escort who had left Dover earlier that day, appeared next to me. His “cargo” was going to be loaded onto my plane for its continuing leg. We stood side by side in the dark and executed a slow salute as Chance was removed from the plane. The cargo crew at Minneapolis kept Phelps’ shipping case separate from all the other luggage as they waited to take us to the cargo area. I waited with the soldier, and we saluted together as his fallen comrade was loaded onto the plane.

My trip with Chance was going to be somewhat unusual in that we were going to have an overnight stopover. We had a late start out of Dover, and there was just too much traveling ahead of us to continue on that day. (We still had a flight from Minneapolis to Billings, MT, then a 5-hour drive to the funeral home. That was to be followed by a 90-minute drive to Chance’s hometown.)

I was concerned about leaving him overnight in the Minneapolis cargo area. My 10-minute ride from the tarmac to the cargo holding area eased my apprehension. Just as in Philadelphia, the cargo guys in Minneapolis were extremely respectful and seemed honored to do their part. While talking with them, I learned that the cargo supervisor for Northwest Airlines at the Minneapolis airport is a lieutenant colonel in the Marine Corps Reserves. They called him for me and let me talk to him.

Once I was satisfied that all would be okay for the night, I asked one of the cargo crew if he would take me back to the terminal so that I could catch my hotel’s shuttle. Instead, he drove me straight to the hotel himself. At the hotel, the lieutenant colonel called me and said he would personally pick me up in the morning and bring me back to the cargo area.

Before leaving the airport, I had told the cargo crew that I wanted to come back to the cargo area in the morning rather than go straight to the passenger terminal. I felt bad for leaving Chance overnight and wanted to see the shipping container where I had left it for the night. It was fine.

The lieutenant colonel made a few phone calls then drove me around to the passenger terminal. I was met again by a man from the cargo crew and escorted down to the tarmac. The pilot of the plane joined me as I waited for them to bring Chance from the cargo area. The pilot and I talked of his service in the Air Force and how he missed it.

I saluted as Chance was moved up the conveyor and onto the plane. It was to be a while before the luggage was to be loaded, so the pilot took me up to board the plane where I could watch the tarmac from a window. With no other passengers yet onboard, I talked with the flight attendants and one of the cargo guys. he had been in the Navy and one of the attendants had been in the Air Force. Everywhere I went people were continuing to tell me of their relationship to the military. After all of the baggage was aboard, I went back down to the tarmac, inspected the cargo bay, and watched them secure the door.

When we arrived at Billings I was again the first off the plane. This time Chance’s shipping container was the first item out of the cargo hold. The funeral director had driven 5 hours up from Rivcrton, WY to meet us. He shook my hand as if I had personally lost a brother.

We moved Chance to a secluded cargo area. Now it was time for me to remove the shipping container and drape the flag over the casket. I had predicted that this would choke me up, but I found I was more concerned with proper flag etiquette than the solemnity of the moment. Once the flag was in place, I stood by and saluted as Chance was loaded onto the van from the funeral home.

I was thankful that we were in a small airport and the event seemed to go mostly unnoticed. I picked up my rental car and followed Chance for 5 hours until we reached Riverton. During the long trip I imagined how my meeting with Chance’s parents would go. I was very nervous about that.

When we finally arrived at the funeral home, I had my first face-to-face meeting with the casualty assistance calls officer (CACO). It had been his duty to inform the family of Chance’s death. he was on the inspector-instructor staff of an infantry company in Salt Lake City, UT, and I knew he had had a difficult week.

Inside, I gave the funeral director some of the paperwork from Dover and discussed the plan for the next day. The service was to be at 1400 in the high school gymnasium up in Dubois-population about 900-some 90 miles away. Eventually, we had covered everything. The CACO had some items that the family wanted to be inserted into the casket, and I felt I needed to inspect Chance’s uniform to ensure everything was proper. Although it was going to be a closed casket funeral, I still wanted to ensure his uniform was squared away.

Earlier in the day I wasn’t sure how I’d handle this moment. Suddenly, the casket was open, and I got my first look at Chance Phelps. His uniform was immaculate-a tribute to the professionalism of the Marines at Dover. I noticed that he wore six ribbons over his marksmanship badge; the senior one was his Purple Heart. I had been in the Corps for over 17 years, including a combat tour, and was wearing eight ribbons. This PFC, with less than a year in the Corps, had already earned six.

The next morning, I wore my dress blues and followed the hearse for the trip up to Dubois. This was the most difficult leg of our trip for me. I was bracing for the moment when I would meet his parents and hoping I would find the right words as I presented them with Chance’s personal effects.

We got to the high school gym about 4 hours before the service was to begin. The gym floor was covered with folding chairs neatly lined in rows. There were a few townspeople making final preparations when I stood next to the hearse and saluted as Chance was moved out of the hearse. The sight of a flag-draped coffin was overwhelming to some of the ladies.

We moved Chance into the gym to the place of honor. A Marine sergeant, the command representative from Chance’s battalion, met me at the gym. His eyes were watery as he relieved me of watching Chance so that I could go eat lunch and find my hotel.

At the restaurant the table had a flier announcing Chance’s service–Dubois High School gym, 2 o’clock. It also said that the family would be accepting donations so that they could buy flak vests to send to troops in Iraq.

I drove back to the gym at a quarter after one. I could’ve walked-you could walk to just about anywhere in Dubois in 10 minutes. I had planned to find a quiet room where I could take his things out of their pouch and untangle the chain of the Saint Christopher medal from the dog tag chains and arrange everything before his parents came in. I had twice before removed the items from the pouch to ensure they were all there-even though there was no chance anything could’ve fallen out. Each time the two chains had been quite tangled. I didn’t want to be fumbling around trying to untangle them in front of his parents. Our meeting, however, didn’t go as expected.

I practically bumped into Chance’s step-mom accidentally, and our introductions began in the noisy hallway outside the gym. In short order I had met Chance’s step-mom and father, followed by his step-dad and, at last, his mom. I didn’t know how to express to these people my sympathy for their loss and my gratitude for their sacrifice. Now, however, they were repeatedly thanking me for bringing their son home and for my service. I was humbled beyond words.

I told them that I had some of Chance’s things and asked if we could try to find a quiet place. The five of us ended up in what appeared to be a computer lab-not what I had envisioned for this occasion.

After we had arranged five chairs around a small table, I told them about our trip. I told them how, at every step, Chance was treated with respect, dignity, and honor. I told them about the staff at Dover and all the folks at Northwest Airlines. I tried to convey how the entire Nation, from Dover to Philadelphia, to Minneapolis, to Billings, and to Riverton expressed grief and sympathy over their loss.

Finally, it was time to open the pouch. The first item I happened to pull out was Chance’s large watch. It was still set to Baghdad time. Next were the lanyard and the wooden cross, then the dog tags and the Saint Christopher medal. This time the chains were not tangled. Once all of his items were laid out on the table, I told his mom that I had one other item to give them. I retrieved the flight attendant’s crucifix from my pocket and told its story. I set that on the table and excused myself. When I next saw Chance’s mom she was wearing the crucifix on her lapel.

By 1400 most of the seats on the gym floor were filled and people were finding seats in the fixed bleachers high above the floor. There were a surprising number of people in military uniform. Many Marines had come up from Salt Lake City. Men from various Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) posts and the Marine Corps League occupied multiple rows of folding chairs. We all stood as Chance’s family took their seats in the front.

It turned out that Chance’s sister, a petty officer in the Navy, worked for a rear admiral-the chief of naval intelligence-at the Pentagon. The admiral had brought many of the sailors on his staff with him to Dubois pay respects to Chance and to support Chance’s sister. After a few songs and some words from a Navy chaplain, the admiral took the microphone and told us how Chance had died.

Chance was an artillery cannoneer, and his unit was acting as provisional military police outside of Baghdad. Chance had volunteered to man a .50 caliber machinegun in the turret of the leading vehicle in a convoy. The convoy came under intense fire, but Chance stayed true to his post and returned fire with the big gun, covering the rest of the convoy, until he was fatally wounded.

Then the commander of the local VFW post read some of the letters Chance had written home. In letters to his mom he talked of the mosquitoes and the heat. In letters to his stepfather he told of the dangers of convoy operations and of receiving fire.

The service was a fitting tribute to this hero. When it was over, we stood as the casket was wheeled out with the family following. The casket was placed onto a horse-drawn carriage for the mile-long trip from the gym, down the main street, then up the steep hill to the cemetery. I stood alone and saluted as the carriage departed the high school. I found my car and joined Chance’s convoy.

The town seemingly went from the gym to the street. all along the route the people had lined the street and were waving small American flags. The flags that were otherwise posted were all at halfstaff. For the last quarter mile up the hill, local boy scouts, spaced about 20 feet apart, all in uniform, held large flags. At the foot of the hill I could look up and back and see the enormity of our procession. I wondered how many people would be at this funeral if it were in, say, Detroit or Los Angeles-probably not as many as were here in little Dubois.

The carriage stopped about 15 yards from the grave, and the military pallbearers and the family waited until the men of the VFW and Marine Corps League were formed up and school buses had arrived carrying many of the people from the procession route. Once the entire crowd was in place, the pallbearers came to attention and began to remove the casket from the caisson. As I had done all week, I came to attention and executed a slow ceremonial salute as Chance was being transferred from one mode of transport to another.

From Dover to Philadelphia, Philadelphia to Minneapolis, Minneapolis to Billings, Billings to Riverton, and Riverton to Dubois, we had been together.

Now, as I watched them carry him the final 15 yards, I was choking up. I felt that as long as he was still moving he was somehow still alive. Then they put him down above his grave. he had stopped moving.

Although my mission had been officially complete once I turned him over to the funeral director at the Billings airport, it was his placement at his grave that really concluded it in my mind. Now he was home to stay, and I suddenly felt at once sad, relieved, and useless.

The chaplain said some words that I couldn’t hear and two Marines removed the flag from the casket and slowly folded it for presentation to his mother. When the ceremony was over, Chance’s father placed a ribbon from his service in Vietnam on Chance’s casket. His mother approached the casket and took something from her blouse and put it on the casket. I later saw that it was the flight attendant’s crucifix. Eventually, friends of Chance’s moved closer to the grave. A young man put a can of Copenhagen on the casket, and many others left flowers.

Finally, we all went back to the gym for a reception. There was enough food to feed the entire population for a few days. In one corner of the gym there was a table set up with lots of pictures of Chance and some of his sports awards.

People were continually approaching me and the other Marines to thank us for our service. Almost all of them had some story to tell about their connection to the military. About an hour into the reception, I had the impression that every man in Wyoming had, at one time or another, been in the Service.

It seemed like every time I saw Chance’s mom she was hugging a different well-wisher. As time passed, I began to hear people laughing. We were starting to heal.

After a few hours at the gym, I went back to the hotel to change out of my dress blues. The local VFW post had invited everyone over to “celebrate Chance’s life.” The post was on the other end of town from my hotel, and the drive took less than 2 minutes. The crowd was somewhat smaller than what had been at the gym, but the post was packed.

Marines were playing pool at the two tables near the entrance and most of the VFW members were at the bar or around the tables in the bar area. The largest room in the post was a banquet/dining/dancing area, and it was now called “The Chance Phelps Room.” Above the entry were two items-a large portrait of Chance in his dress blues and the eagle, globe, and anchor. In one corner of the room there was another memorial to Chance. There were candles burning around another picture of him in his blues. On the table surrounding his photo were his Purple Heart citation and his Purple Heart medal. There was also a framed copy of an excerpt from the Congressional Record. This was an elegant tribute to Chance Phelps delivered on the floor of the United States House of Representatives by Congressman Scott Mclnnis of Colorado. Above it all was a television that was playing a photo montage of Chance’s life from small boy to proud Marine.

I did not buy a drink that night. As had been happening all day-indeed all week-people were thanking me for my service and for bringing Chance home. Now, in addition to words and handshakes, they were thanking me with beer. I fell in with the men who had handled the horses and horse-drawn carriage. I learned that they had worked through the night to groom and prepare the horses for Chance’s last ride. They were all very grateful that they were able to contribute.

After a while we all gathered in The Chance Phelps Room for the formal dedication. The post commander told us of how Chance had been so looking forward to becoming a life member of the VFW. Now, in The Chance Phelps Room of the Dubois VFW Post, he would be an eternal member. We all raised our beers and The Chance Phelps Room was christened.

Later, as I was walking toward the pool tables, a staff sergeant from the Reserve unit in Salt Lake City grabbed me and said, “Sir, you gotta hear this.” There were two other Marines with him, and he told the younger one, a lance corporal, to tell me his story. The staff sergeant said the lance corporal was normally too shy and modest to tell it, but now he’d had enough beer to overcome his usual tendencies.

As the lance corporal started to talk, an older man joined our circle. He wore a baseball cap that indicated he had been with the 1st Marine Division in Korea. Earlier in the evening he had told me about one of his former commanding officers, a Col Puller.

So, there I was, standing in a circle with three Marines recently returned from fighting with the 1st Marine Division in Iraq and one not so recently returned from fighting with the 1st Marine Division in Korea. I, who had fought with the 1st Marine Division in Kuwait, was about to gain a new insight into our Corps.

The young lance corporal began to tell us his story. At that moment, in this circle of current and former Marines, the differences in our ages and ranks dissipated-we were all simply Marines.

His squad had been on a patrol through a city street. They had taken small arms fire and had literally dodged a rocket-propelled grenade round that sailed between two Marines. At one point they received fire from behind a wall and had neutralized the sniper with a shoulder-launched multipurpose assault weapon (SMAW) round. The back blast of the SMAW, however, kicked up a substantial rock that hammered the lance corporal in the thigh, only missing his groin because he had reflexively turned his body sideways at the shot.

His squad had suffered some wounded and was receiving more sniper fire when suddenly he was hit in the head by an AK-47 round. I was stunned as he told us how he felt like a baseball bat had been slammed into his head. he had spun around and fell unconscious. When he came to he had a severe scalp wound, but his Kevlar helmet had saved his life. he continued with his unit for a few days before realizing he was suffering the effects of a severe concussion.

As I stood there in the circle with the old man and the other Marines, the staff sergeant finished the story. he told of how this lance corporal had begged and pleaded with the battalion surgeon to let him stay with his unit. In the end, the doctor said there was just no way-he had suffered a severe and traumatic head wound and would have to be medically evacuated.

The Marine Corps is a special fraternity. There are moments when we are reminded of this. Interestingly, those moments don’t always happen at awards ceremonies or in dress blues at Birthday Balls. 1 have found, rather, that they occur at unexpected times and places-next to a loaded moving van at Camp Lejeune’s base housing, in a dirty command post tent in northern Saudi Arabia, and in a smoky VFW post in western Wyoming.

After the story was done, the lance corporal stepped over to the old man, put his arm over the man’s shoulder and told him that he, the Korean War veteran, was his hero. The two of them stood there with their arms over each other’s shoulders, and we were all silent for a moment. When they let go, I told the lance corporal that there were recruits down on the yellow footprints tonight who would soon be learning his story.

I was finished drinking beer and telling stories. I found Chance’s father and shook his hand one more time. Chance’s mom had already left, and I deeply regretted not being able to tell her goodbye.

I left Dubois in the morning before sunrise for my long drive back to Billings. It had been my honor to take Chance Phelps to his final post. Now he is on the high ground overlooking his town.

I miss him.

![]()

![]()

Thank you for sharing.

Because in the USA, there is no such crime as “hate speech”. The 1st Amendment of the US Constitution guarantees freedom of speech, no matter how repugnant or reprehensible. The 1st also guarantees freedom of religion. There are local laws for criminal threats/terrorist threats, but those have very specific criteria.